The Courage and the Scourge of Caring: Coal Miners’ Earthquake Search and Rescue Work

E. İrem Az

17 March 2025The Soma coal miners translated their underground skills into life-saving care after the February 6, 2023, earthquakes, acting swiftly where the state failed. Using traditional mining techniques, they reinforced the rubble, creating moments of survival through expertise, solidarity, and sheer physical courage. Their intervention exposes how care under capitalism remains reactive—yet, when organized, it holds the potential to resist collapse and build a different future.

“If you push on a tree from above, it’ll tell you, “Get out of here!” It makes a cracking sound, like, “You’re in a dangerous spot, I can’t hold on, get out!” Because after working down here [in the mines] with these things [techniques] for so long, it becomes experience. It’s [the tree] giving you a warning. With iron, though, you can’t hear anything. It just clinks and slides away, and you get caught underneath. But with a tree, that’s not the case. A tree always gives you a heads-up. It has a bit of give to it. It tells you, “Move away from here.” When you reinforce the building [with parts of a tree], it also—when it gives way, it’s telling the building, “Stop!” It says, “I’m not letting you go.” When you support [the space you’ve cleared under the rubble] with a tree, there’s no chance of movement. Even if the building slides, it’ll slide sideways along with the tree. It protects you that way.

And in the meantime, you get the hell out of there.”

—Meriç, an experienced coal miner from Soma who participated in search and rescue operations after the twin earthquakes of February 6, 2023.

Is it possible to translate our work abilities and skills, which currently allow us to generate value within capitalism, into another kind of value—a value that contributes to a regime of commons and collectively-organized care? And is it possible to do this before an urgent need emerges—in order to make caring an act beyond an afterthought, beyond a “curative” measure that is taken only after so-called crises and pain within capitalism? Coal miners in Turkey responded to these two questions through action, following the twin earthquakes of February 6, 2023. I conducted oral history interviews with nine of them in the summer 2024, as part of my ongoing fieldwork in the Soma Basin and the Antakya province of the earthquake-stricken southeastern Turkey, funded by the Disaster Studies Initiative at Harvard’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies.[1] The Turkish party-state, led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (Justice and Development Party, henceforth the AKP), stopped counting the number of deaths when it reached 53,537 in Turkey alone—while the estimated number of people who died in Syria is between 5,951 and 8,476.

Most of the time, my answer to the initial questions is no. This is not a cynical or pessimistic response, nor one that refuses to acknowledge the value of unpaid and underpaid care work performed by dispossessed women and other working people. On the contrary, it is a “no” that follows the evidence provided by domestic workers, unpaid women houseworkers, coal miners—including my interlocutors in the Soma Coal Basin of Turkey—and others whose labor and bodies are exploited daily in novel ways to sustain capitalist economies, currently through neoliberal forms and processes, which David Graeber once called “the curse of the working classes” because “generations of political manipulation have finally turned [their] sense of solidarity into a scourge.” The impact of their extraordinary work is often limited to being curative, not due to a lack of effort or potential, but because their forms of care emerge as requirements for survival and endurance within structures to which they are confined.

The kinds of care enacted by working and caring people worldwide have the potential to save, nourish and maintain countless people and lives. Yet, this work is restricted by the conditions that make it required for the survival of many. Within neoliberal capitalism, the burden of caring for others is placed on the shoulders, arms, legs, necks, backs, and the entire bodies and personhoods of the exploited and the dispossessed. The coal miners of Turkey who conducted the most competent and effective earthquake search and rescue work in the aftermath of February 6, 2023, testify to this fact. The state-led search and rescue teams were appallingly absent during the first three to four days following February 6—especially in the city of Hatay—which is now a well-documented fact. When they did show up, their incompetence was reported by volunteers and survivors alike. Meanwhile, the Turkish party-state refused to work with unions and civil society organizations that were not pro-AKP in the organization of disaster response and relief.

Anticipating this absence, as they were familiar with the protective and regulatory state bodies, miners from Soma—and later from Zonguldak and other mining cities in Turkey—immediately went to the earthquake zone. They translated their ability to work in underground mines into acts of care through earthquake search and rescue operations. Soma miners used particular traditional coal mining techniques, such as the pigsty system [domuz damı] and the pillar-and-stall system [kolon ve galeri sistemi or klasik bağ sistemi], to navigate under and through the rubble, saving lives or recovering bodies. They used parts of trees to build these systems into, through, and beneath the rubble. Miners drew my attention to both these techniques and their corporeal-technical skills, which are underpinned by courage, and to some extent, masculinity. They argued that they had this courage precisely because they worked in the coal mines of Turkey—a kind of courage that, as both they and earthquake survivors in Antakya observed, was lacking in national and foreign professional search and rescue teams.

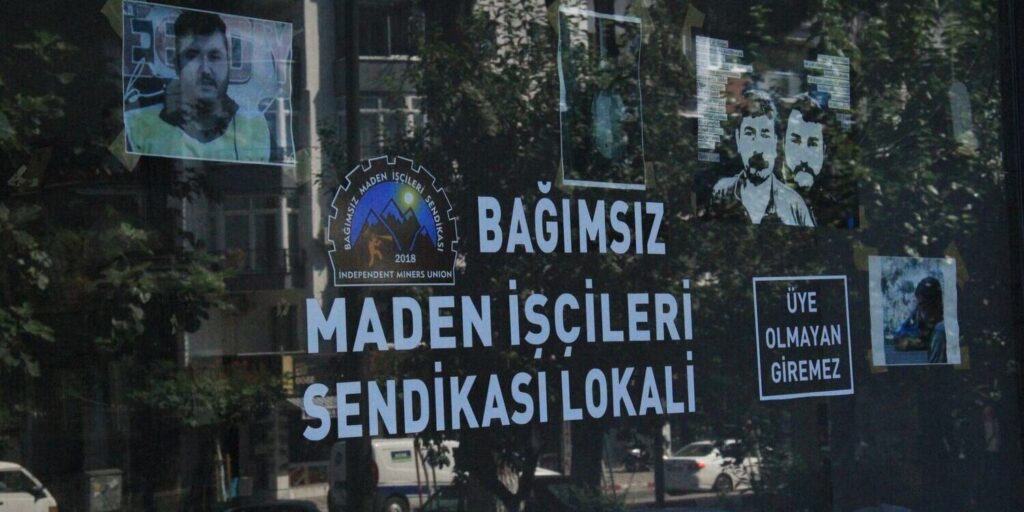

Most of my interlocutors who conducted search and rescue operations are members of Bağımsız Maden İşçileri Sendikası (Independent Miners’ Union, henceforth the BMİS), which was established by miners themselves in 2018—while I was living and conducting fieldwork in the Soma Basin. These unionized miners gathered at the union office immediately after news channels began reporting on the scale of destruction in the earthquake zone. They initially sought a bus, along with manual and electric digging tools, from Soma Municipality. After their request was denied, they reached out to Akhisar Municipality—the municipality of a nearby town currently governed by the main opposition party, Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (People’s Republican Party, or CHP)—which quickly arranged a bus for the initial group of miners (and later for the subsequent groups).

The initial group of 30 miners left Soma on the evening of February 6 and arrived in Samandağ, in the city of Hatay (also known as the ancient city of Antakya/Antioch), on the evening of February 7. Traveling with very limited resources and digging tools, including their own personal ones, and finding whatever tools they could in Antakya, this first group rescued 31 people alive and recovered an uncounted number of bodies. The second group of 29 miners left Soma on February 7 and arrived in Elbistan, Maraş, the following evening. They were stalled for three days by AFAD (Afet Acil Durum Müdürlüğü [Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency]) before starting to operate on the rubble where living people were still trapped. They rescued 6 people alive and recovered an uncounted number of bodies. The final group of 11 miners arrived in Hatay on the 7th day following February 6, with the mission of recovering bodies whole, as state officials had already announced that they would soon begin removing the rubble with excavators, regardless of the bodies inside. These 11 miners stayed in the region until the state-organized removal of the rubble began approximately two and a half weeks after February 6. My union organizer interlocutors told me that they also provided logistical support and other assistance to miners from the cities of Çorum and Kütahya, who then traveled to the earthquake zone. However, they did not have information on the number of lives saved by these groups.

Among my interlocutors, only two traveled to the earthquake zone through the organization of their employers/mining companies, with better conditions and equipment. However, my unionized interlocutors, including the President of BMİS, Gökay Çakır, argue that it was their own initiative—taken immediately in recognition of the time-sensitive nature of earthquake response—and the public calls they made to all mining companies across Turkey, urging them to send their workers to the earthquake zone, that ultimately pressured the mining companies in Soma to follow suit. Their courage to risk their lives to rescue people, along with the popularity their work garnered in the public eye, is what forced the hands of the administrations of mining companies.

I consider courage as a skill, or more specifically, as a corporeal skill—though no human skill is ever disembodied. For coal miners, courage is forged through dangerous working conditions and working-class masculinities, and it is translatable to a caring skill. As long as we are within capitalism, it does not seem possible to make care an act beyond an afterthought, a “curative” measure. At the same time, certain acts of care, such as the volunteer search and rescue work performed by coal miners in Turkey, are creative and future-oriented, while also addressing urgent, life-saving needs under neoliberal regimes of austerity and state withdrawal, since they create models for a post-capitalist time in which people might forge ways to translate their exchange-value-generating skills into skills of caring for others and contributing to the commons.

The significant political impact and the promising futurity of coal miners’ search and rescue work stem from their defiance of several distinctions that continue to shape the political, economic, and cultural value systems within capitalism: the divide between manual and intellectual labor, repetition and creativity, and the separation of person, nature, and tool/technical object. The power of what they did is rooted in the fact that, at the time of the earthquake and still today, they were—and are—organized. They were able to act swiftly and save many lives thanks to their ability to take coordinated action against all odds. With each passing day, more and more of us, including those in more privileged groups in the Western world, find ourselves searching for ways to engage in collective and organized action. The search and rescue work of the coal miners in Turkey serves as both a reminder and a warning to many of us: to act quickly and act together.

[1] Though I have conducted oral history interviews with only nine coal miners so far, my arguments are based on both my 18-month ethnographic fieldwork in the Soma Basin (2018–2019) and my ongoing research in the Soma Basin and Antakya province, which, as of today, includes 38 oral history interviews with coal miners and earthquake survivors conducted since February 2023.

The two photos on the cover and within the blog are from Antakya and the Independent Miners’ Union office in Soma. They were taken by E. Irem Az.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.