Medicaid Football

Nancy Folbre

16 June 2025Putting Congressional debate over health insurance into context.

This spring, Medicaid (the joint federal and state program that provides at least some health insurance to low-income persons in the United States) became a political football in the Republican effort to slash federal social spending.

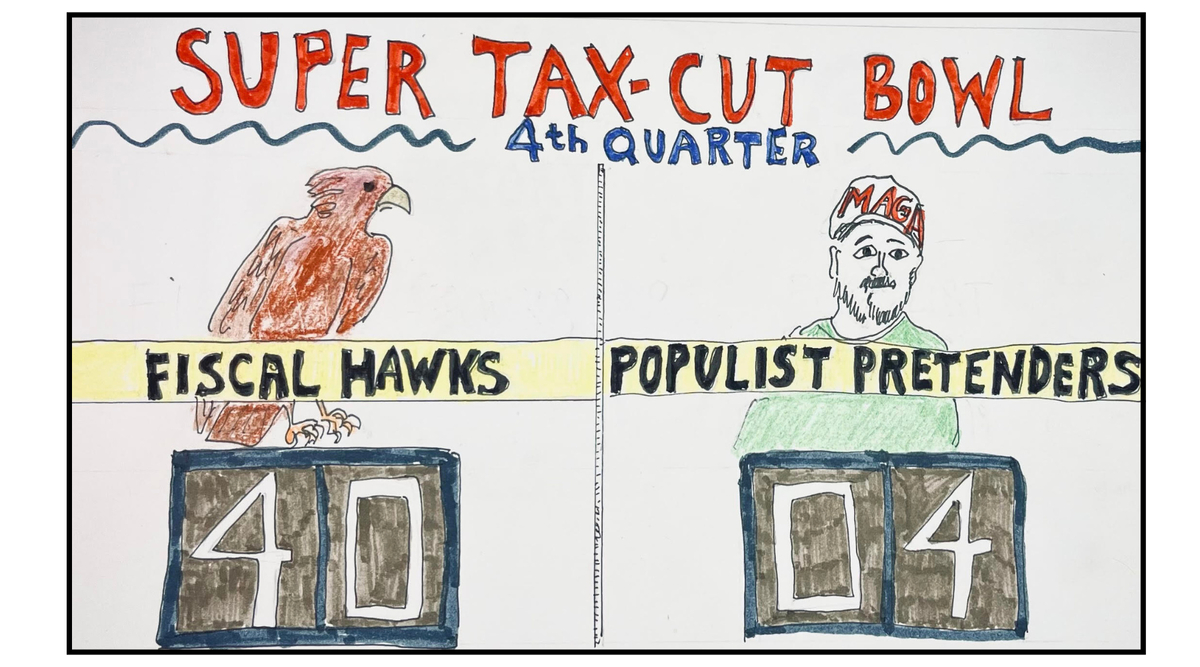

Due to their underrepresentation in Congress, Democrats had little skin in this game, despite their loud protests from the sidelines. Instead, the scrimmage featured two wings of the Republican party allied primarily by their desire for tax cuts: fiscal hawks insisting on huge cuts in discretionary programs such as Medicaid, and populist pretenders, voicing concern that many of their own constituents would be harmed.

While the game is not yet over, whatever compromise emerges will dress significant cuts in Medicaid spending in the pious garb of a proposal to proposal to punish able-bodied shirkers. While it’s important to understand this strategy, it’s also useful to consider the larger playing field.

The United States stands out among affluent countries not only for its failure to provide universal coverage, but also for its stunning inefficiency. We spend a higher percentage of our Gross Domestic Product on health care than any other country in the world, yet our average life expectancy is relatively low.

For some groups, average life expectancy has actually declined, due to increases in the number of deaths due to suicide, drug addiction, and alcoholism—sometimes termed “deaths of despair.” Mortality from sheer carelessness is also high—firearms are now the leading cause of death for children between the ages of one and 17 in the United States. Lack of access to insurance, combined with poor health care delivery, has contributed to significant disparities based on income, race, and place of residence. Rich, white, urban residents fare much better than others.

Differences in income have tangible effects. One study that followed individuals over an eight-year period found that those with a household income greater than $50,000 were likely to live 10 years longer than those with less than $15,000.

How did we land in a game that is both inefficient and unfair? Access to health care insurance is a team sport, where individuals share risks by investing in shared coverage, but benefit by excluding both low-income and unhealthy individuals, which would increase their group costs. Greater inequality in both income and health magnifies the incentives for exclusion. In the United States, exclusion has been furthered by a “divide and conquer” strategy adopted by a tacit coalition of large employers and the well-to-do.

Republicans have opposed public health care provision whenever politically feasible to do so. In pushing for incremental change, Democrats have made small gains but have proved unwilling to advocate for major reforms such as Medicare for All.

The political pressure to meet health care needs has been reduced by strategic co-optation—singling out specific groups for benefits to discourage larger coalitions. The Medicare system, which provides “single-payer” health care for those 65 and over, wins votes because everyone hopes to grow old.

Medicaid, which was signed into law in 1965, was designed to reach those who could not afford to pay for insurance on their own but the program was restricted to those with extremely low incomes and set up to allow states considerable flexibility to limit access. Early expansions to Medicaid, such as the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIPH) established in 1997, gave states federal matching funds to expand eligibility for children, seen both as especially “deserving” and as future workers and taxpayers.

Congress was able to ignore much of the working-age population because tax incentives led many employers to offer health insurance to many of their employees. This constituency was concentrated among full-time employees of large firms. Members of relatively powerful trade unions were also able to bargain for relatively generous coverage. Employer coverage was far from ideal—loss of a job could mean permanent loss of health insurance coverage. Still, it reduced incentives to support greater public provision.

However, health care costs increased substantially over time, partly as a result of new technologies for the treatment of heart disease and cancer, and partly as a result of the high administrative costs of the fragmented payment system. Many people were priced out of the health insurance market, and private insurance companies increased their efforts to exclude customers with pre-existing health conditions. Both trends intensified calls for change.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010, (sometimes dubbed Obamacare), made it illegal for insurance companies to deny coverage to those with pre-existing conditions and provided significant health insurance subsidies for those not eligible for Medicaid. It also offered states significant financial incentives to expand Medicaid eligibility for working-age adults earning near-poverty wages. Ten states—all under Republican governance with relatively large low-income Black and/or Hispanic populations—declined this offer, though they have recently begun to feel pressure from both voters and employers.

In general, Republican or so-called red states have implemented policies less conducive to improvements in public health—and average life expectancy—than blue states. Variation in the adoption and timing of expansions in Medicaid eligibility provides a particularly compelling example. A recent paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research finds that Medicaid expansions reduced the mortality of the total low-income adult population by 2.5%, and that new enrollees probably reduced their mortality by more than 20%.

Making this kind of information more visible could be a game changer. The fragmentation of our health care system discourages public mobilization. The complexity of Medicaid requirements is also a deterrent. Since eligibility for it is defined in terms of some percentage of a poverty-level income, most people assume it is restricted to the officially poor. Few people have a clear picture of who is eligible in their state, and who is not—much less a sense of the health payoffs of expansion. As a result, it’s hard for them to know which team they are on.

A concerted push for a single-payer public health insurance system, such as Medicare for All, would benefit a very large constituency by reducing administrative costs, expanding coverage, and improving health outcomes. On April 29 of this year, Senator Bernie Sanders and Representatives Pramila Jayapal and Debbie Dingell introduced legislation (yet again) in support of this goal, with endorsements from National Nurses United and Physicians for a National Health Program. Yet neither congressional Democrats nor the mainstream media are paying much attention.

I’m not a big football fan, but those who are say that “the best defense is a good offense.” Whatever happens to the proposed Medicaid cuts, we need to fight our way toward a bigger (and more beautiful) goal.

Artwork by Nancy Folbre. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.