The Nappy Revolution

Kelly Dombroski

18 November 2024Caring for Life: a new book that re-values nappy-free infant hygiene care practices

Earlier this year, I had the great pleasure of releasing my new book, Caring for Life: A Postdevelopment Politics of Hygiene. This book is a culmination of years of research and exploration into the rich, often overlooked practical knowledge of communities frequently labelled as “undeveloped.” The book draws on decolonial and postdevelopment scholarship to decentre Western norms in thinking about practices of hygiene and sanitation in the far west of China. I argue that the nappy/diaper-free hygiene practices used by communities in the far west of China offer potential for rethinking hygiene and sanitation in the Western world, rather than necessarily being slated for abandonment under the water-based hygiene norms assumed by the Sustainable Development Goals.

The book also offers the example of a hybrid research collective of caregivers in Australia and New Zealand learning how to adopt the nappy/diaper-free practice in their own contexts, to reduce their use of disposable nappy products and the labour of washing reusables. It re-values the care practices of people often overlooked in modernisation approaches to development– grandmothers, mothers and other caregivers doing the mundane and relational work of caring for everyday hygiene – and shows how these overlooked groups are experimenting in social change in important prefigurative ways.

Hygiene and sanitation are difficult areas to apply a postdevelopment approach that rejects the assumption that Western norms are best – since the dominance of Western norms in the peer reviewed biomedical literature makes it hard for other norms to be seen as potentially sanitary. For example, Western norms of toilet-training assume a child cannot be toilet-trained until they are verbal, because that is when Western cultures start training. Until recently, all the scientific literature in the English language assumed this, despite vast swathes of the Majority World (Global South) practicing forms of infant hygiene centred around non-verbal communication and eschewing (or using significantly less) nappies/diapers.

Even now, when nappy-free infant hygiene has a presence in the scientific literature, embodied feelings of confusion and disgust can get in the way of valuing such a care practice, at least for cultural outsiders. This was something I also had to face in my fieldwork.

Embodied Ethnography: The Method Behind the Insights

One of the unique aspects of this book is the methodology I employed, which is detailed in a recent article on embodied ethnography for Asia Pacific Viewpoint. This approach involves using one’s own bodily experiences to understand and document care practices across different cultures. By immersing myself in the daily lives and practices of these communities, and paying attention to when I felt moments of “awkward engagement” present in my body, I was able to gain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of caregiving methods and spaces in China’s far west. While all forms of ethnographic research involve cultural immersion, we are often not trained to pay attention to our own bodies in the same way that we are trained to pay attention to what other people say and do. In postdevelopment action research, like decolonial research, those of us from the Minority World (particularly white people, such as myself) are invited to recognise our own assumptions and biases, and of course, work to challenge these and respond to criticisms. In my ‘embodied ethnography’, I extend this thinking to pay attention to what is happening in my body, and what it reveals about my assumptions and biases.

I drew on Anna Tsing’s understanding of awkward engagement between travelling universals, but expanded it to think about how we embody our cultural “universals” in moments of disgust, panic, fear, awkwardness when our usual embodied norms are challenged. For example, in my research, this was often about the differences in how babies and caregivers interact with urban outdoor space in China as opposed to New Zealand, where I come from. I vividly recall the feeling of awkwardness and confusion the first time I saw a baby held out to urinate on a tiled floor, and, although it was immediately mopped up, the feeling of awkwardness and shame I harboured as I realised I had been putting my own baby on the floor to play and no one else ever did. Paying attention to these embodied feelings of awkwardness helped me recognise when spaces of care were being used in ways that revealed different cultural realities of hygiene, bodies, and health.

Caring for life: studying waste and social change beyond infant hygiene

Although the research began with embodied encounters with hygiene, the question I really try to answer in the book is how does social change happen? I was fascinated with how nappy-free hygiene had resisted apparent westernisation (at least in the place and time of my research) and how people in the Western world were trying to recover and learn these new practices. Through the concrete research work on hygiene, I was able to think further about how change happens through the experimental practices of collectives of people highly motivated to work out new ways of being with and in the world. The collective aspects of adopting nappy-free hygiene emerged through the study of the online forums where caregivers set up mini research experiments, shared results and collated and cared for knowledge about alternative infant hygiene.

But this has inspired my current work too – how do collectives of change-makers work together to develop better ways of being in and with the world and our waste? I’m currently working on a project using the same thinking to explore waste-conscious collective subjectivities emerging through community waste action organisations in Aotearoa New Zealand.

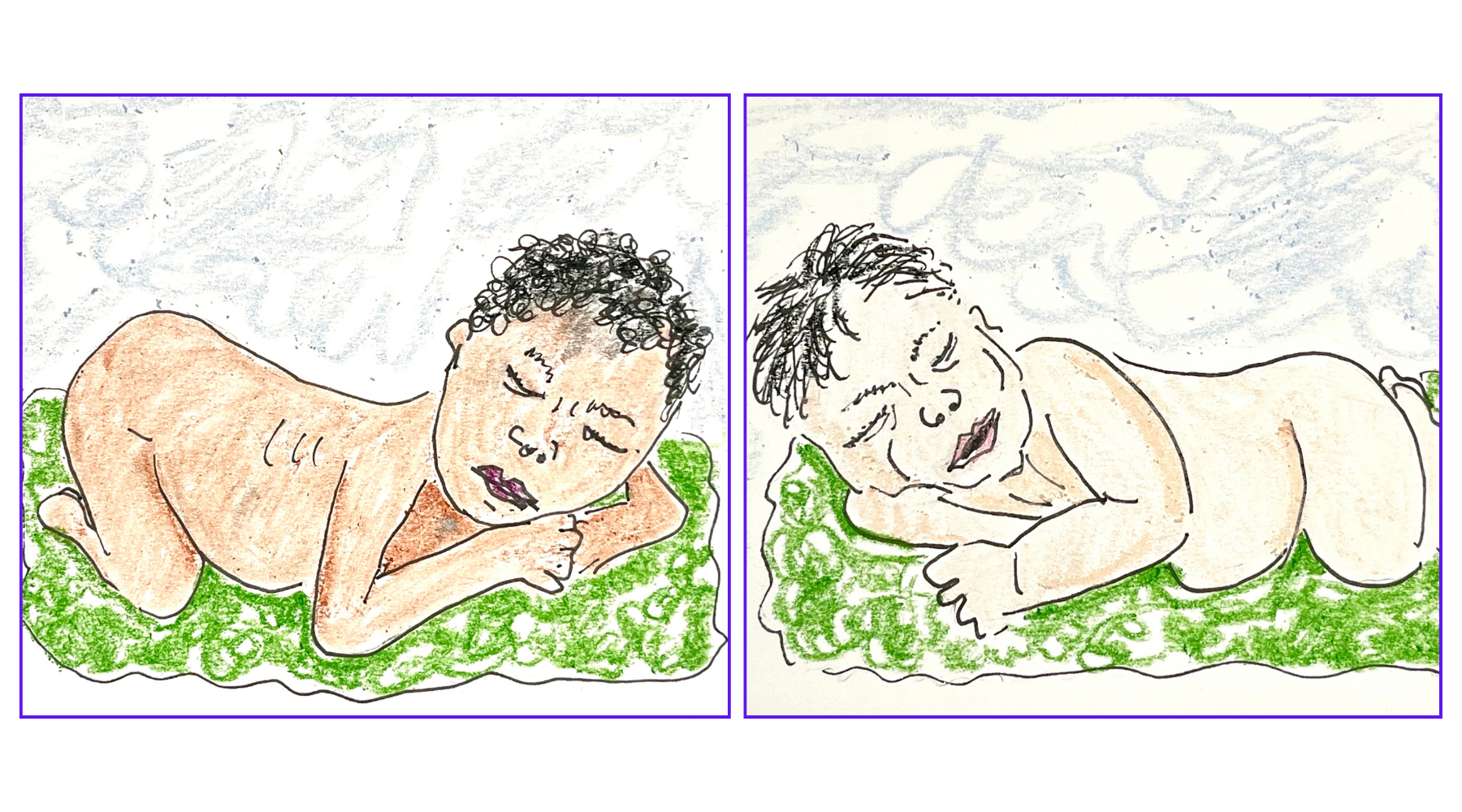

Artwork by Nancy Folbre

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.