Sex, Work, and Care

Alisson Rowland

3 December 2024Sex workers forge critical connections to end gender violence, combat stigma and criminality, and build a more caring world.

December 17th marks the 21st annual International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers, which calls attention to the violence and stigma sex workers experience. Originally instituted as a memorial for sex workers murdered by a serial killer in Seattle, the event has transformed into an annual reminder of the violence people experience due to whorephobia and sexism. This violence can affect anyone, but it is exacerbated by engaging in sex work as well as across power hierarchies, impacting women, people of color, disabled people, and so forth in greater measures. December 17th serves as a reminder that violence against women cannot be solved without addressing violence against sex workers. That task- ameliorating gendered and racialized violence-has been a work in progress. But I want to highlight here the ways the failure to attend to sex work as work, particularly as care work, stifles this goal by discussing the connections between sex work(ers), care work, and political activism.

Conventional understandings of sex work often fall into a victim-criminal binary; sex worker’s are either victims of human trafficking, or deviants corrupting society. This false dichotomy serves to erase sex worker’s agency and devalue their labor, while also drawing attention from actual survivors of trafficking. Popular discourses around sex work are compounded by criminalization in the United States. Though some forms of intimate labor– an umbrella term for various professions which require touch and closeness – are legal, such as body massage and camming, other forms of sex work remain subject to hyper-policing and surveillance.

The COVID-19 pandemic, along with the growing cost-of-living crisis, has contributed to the growth of the commercial sex industry. Though accurate data on the size of the industry is difficult to obtain, many people who engage in sex work often simultaneously have a civilian job. Due to this, issues sex workers experience are not confined to the industry but impact other spaces. This is also true as sex workers move in and out of the industry, often with no one the wiser- after all, someone you know is probably a sex worker. As such, the stakes of whorephobia, the fear and hatred of sex workers, are far-reaching.

Sex workers tend to be people who are already marginalized by the state by virtue of other identities, and criminalization of sex work compounds this. In this way, sex workers’ societal treatment is a litmus test for how precarious communities are treated by the law. Advocating for other issue areas, such as reproductive care or queer rights, requires attending to the condition of sex workers. Increasingly, there is recognition that decriminalization can alleviate the harms many marginalized groups experience. But even as sex work becomes more common in our every day lexicon through adult content creation platforms such as OnlyFans, we have police force in Los Angeles and beyond funneling resources into “anti-trafficking” initiatives targeting street-based sex workers. Arresting people will not “rescue” them. Decriminalization is only one step in ameliorating violence, but it is a necessary one.

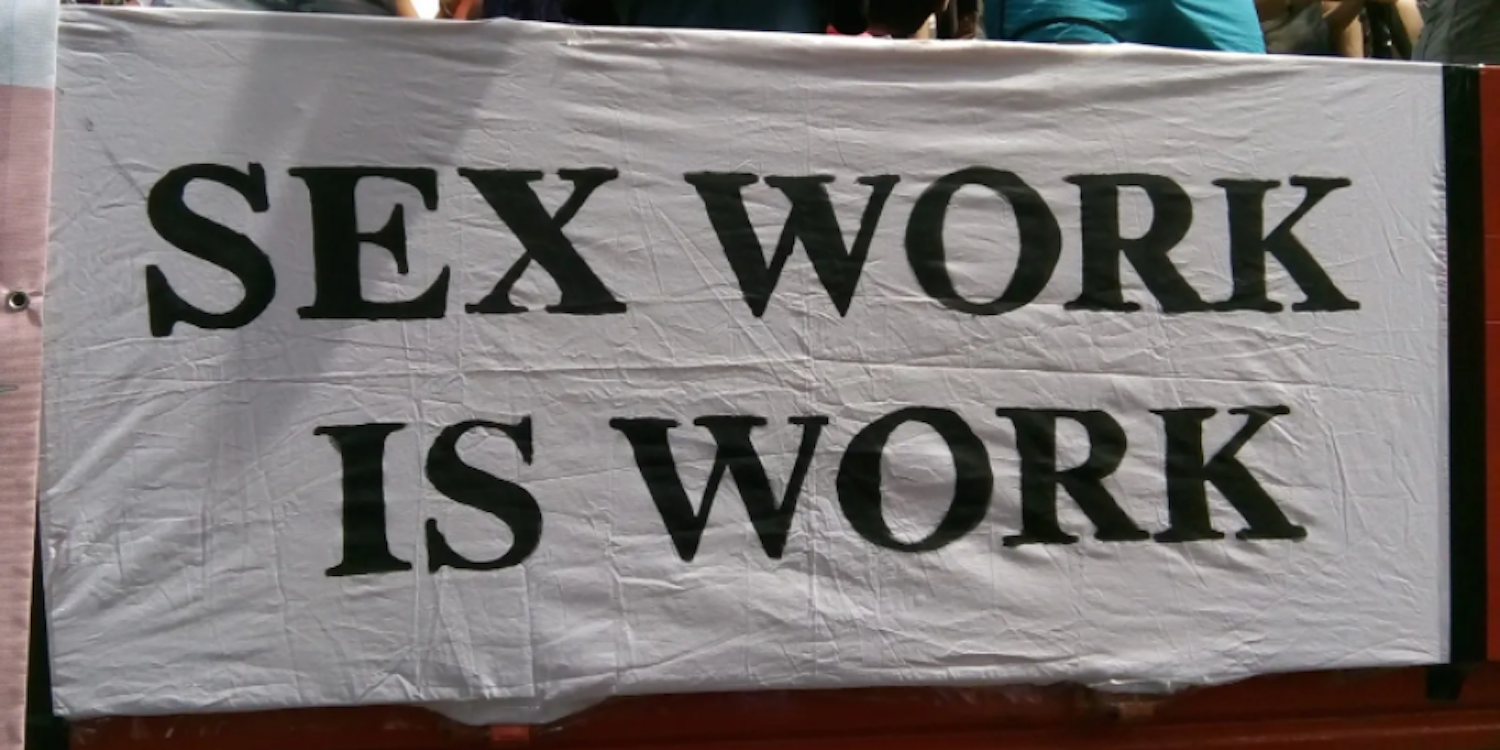

Though sex work is regulated and conceptualized as distinct from other forms of work, the reality is it is a job like any other. Conceptualizing it as such allows discussions of the industry to be un-exceptionalized and the potential for exploitation and harm to be recast into a broader critique of work under capitalism; survival sex work exists because people are forced to work to meet their basic needs. It also allows for understanding sex work as a form of care work. Like other forms of intimate and body labor, sex workers make their living through touch. Similar to these other forms of care work, what they do is part of the day-to-day work that keeps society going.

As others argue, sex work is also more than work. People who enter the industry often do so because they are unable, or uninterested, to work traditional jobs. It allows people who are gender non-conforming or transgender, who are disabled, or who are otherwise excluded from “standard” employment relations to make a living. Many sex workers have also spoken about the role pleasure has played in their work, and how it offers a window into creative exploration. It is a way of participating in work while at the same time refusing it.

While both are compelling ways of understanding sex work, I think it is also useful to consider what sex work is/does distinct from labor as such to truly account for its role as both “labor” and “more than labor.” Sex work offers a window into how we care, how we are in relation to one another. Sex workers occupy a stigmatized and criminalized position in society, and many experience compounding forms of state violence and surveillance. Recognizing sex work as activism allows us to hold space for its role as labor and more-than-labor, while also attending to its transformative potential. Historian April Haynes illustrated the ways sex workers and other intimate laborers have sought to create counter-narratives for hundreds of years. I more fully expand upon the transformative potential of sex work(ers) in a forthcoming article “Care as a Process of Transformation: How Sex Workers Redefine Care.”

The skillset sex workers develop is multi-faceted, and many of the same tools workers use with clients can be applied to organizing; developing and maintaining relationships, navigating tensions and conflict, and consensus building, to name a few. These are critical for working, for caring, and for organizing. A potent example of this interplay is a recent zine publication created by Sex Workers Outreach Project Los Angeles (SWOPLA), and co-published with smingsmingbooks and cashmachinela. ProMomme: A Sex Worker’s Guide to Parenting centers the experiences of sixteen parents and sex workers. Its authentic discussions of relatable topics- from talking to children about sex, to bodily changes pre/post pregnancy, to work-life-care balance- this zine serves to both celebrate and destigmatize intimate labor and child care, and the people who perform it. A documentary that shares the story of how this zine was created is in the works.

Another example of the ways sex workers mobilize to reduce gendered violence is the creation of Sex Worker Abortion Navigation Services (SWANS). Formed in the wake of Roe v. Wade’s repeal, SWANS is a peer-run practical support program that assists current and former sex workers in navigating the reproductive care landscape. In a country that is increasingly criminalizing reproductive care, providing greater access to these necessary services is a political project itself. Being a program run by and for sex workers is also a political commitment to center lived experiences in building up care capacity.

The everyday-ness of sex work is mirrored in workers approach to everyday organizing. Sex worker organizers do not halt their care work when they “clock out” of work, because they realize none of us can if we hope to achieve a more caring world. To hear more about how sex workers and allies are conspiring towards a more caring world, tune in December 17th to a virtual seminar that will feature speakers from Sex Workers Outreach Project Los Angeles (SWOPLA), the Southern California Library, and Third Wave Fund, who will share the work they do to support sex worker’s liberation. The event will be streamed and you can find event details at ISA’s Virtual Events list.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.