Invisible Frontliners: Filipina/o Caregivers in the United States and Collective Care

Valerie Francisco-Menchavez

3 November 2023Before, during the COVID-19 era, and continued to today, Filipino care workers are at the frontlines of assisted living facilities, residential care facilities for the elderly (RCFEs) and as personal attendants to chronically ill and differently abled people in the San Francisco/Bay Area. Because the caregiving industry has stagnated as an under resourced sector of American healthcare, the care workers within it suffer from a host of labor violations. Yet, caregivers have innovated their ability to care for one another.

In the current COVID-19 endemic times in the United States (US), the spikes in transmission and deaths often draw our attention to the health care frontliners made up of mainly the brave doctors and nurses working in hospital settings. Other types of frontline workers who provide health and other kinds of care labor have largely been unacknowledged in their roles holding the line. Given the emaciated systems and policies around long-term care and eldercare in the US, many care workers, formal or informal, are often invisible.

Broadly, Filipino migrants are overrepresented among health care workers in a range of healthcare occupations in the US. While Filipino migrant nurses make up only 4% of the nursing population in the US, nearly a third of the nurses who perished from the COVID-19 virus are Filipino (McFarling 2020). Filipino migrants are also working in auxiliary industries of long-term care and eldercare, and yet the numbers to accurately track the deaths from COVID-19 for caregivers are absent because there is no centralized system to record caregiver employment.

The work of caregiving is already one that is isolated. Caregivers work in a range of settings such as assisted facilities that can have many beds and patients on a single wing or floor; other caregivers work in small teams of 2 or 3 are situated in non-hospital settings, for example, in homes that are turned into facilities for eldercare. While others who are “one-on-one” caregivers conduct visits to private homes. Oftentimes, caregivers are doing the work on their own in private home settings.

Before, during the COVID-19 era, and continued to today, Filipino care workers are at the frontlines of assisted living facilities, residential care facilities for the elderly (RCFEs) and as personal attendants to chronically ill and differently abled people in the San Francisco/Bay Area. Because the caregiving industry has stagnated as an under resourced sector of American healthcare, the care workers within it suffer from a host of labor violations. A investigative report found gross wage and hour violations in residential care facilities for the elderly (RCFE) (Gollan, 2019). Conditions reported in the study are not only detrimental to the health and safety of the workers but “can erode” the quality of care provided to the residents. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing crisis in caregiving that many Filipino caregivers have lived with for decades (Nasol and Francisco-Menchavez, 2021). In a recent study, I found that over 30% of Filipino caregivers do not have regular access to disposable Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in their workplaces (Francisco-Menchavez et al 2020).

Obstacles to and Strategies for Collective Care

Filipino caregivers who experience loneliness and isolation at their workplaces depend on community gathering spaces to find respite. Church and fellowship, Filipino restaurants and ethnic shopping centers, community centers and Filipino ethnic events all served as social gatherings, a relief from the isolation of caregiving work. In the past, caregivers used these spaces to exchange information about jobs, housing, and current events. There, they would celebrate their milestones, birthdays and remit money to their families to the Philippines. This social support network was a robust one that served pragmatic and leisurely purposes.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the characteristic of isolation for caregivers was exacerbated. Some caregivers might integrate movies or meet up with other caregivers and patients for a walk at a park or a nearby mall into their weekly routines before the pandemic. With the lockdowns, caregivers and their patients were unable to leave their premises. Given the population they serve, public places became dangerous for their patients. While their work routines stayed the same, intensifying as news of the virus was spreading, their communal spaces and events disappeared. This lack of contact among community members foreclosed the opportunity to exchange information about the pandemic. Basic information regarding the virus and how to protect oneself was hoisted onto the shoulders of individual caregivers. What caregivers could expect from their employers in terms of safety and health protections were relegated to what employers communicated to their employees. The opportunity to learn what other caregivers were demanding from their employers, and perhaps what employers were willing to provide were shut down because of caregivers’ lack of communal spaces.

As the world turned to Zoom and videoconferencing to transition to remote work and school, caregivers were at a loss. Caregivers were not considered a workforce that could opt out of coming into their workplaces. They were essential workers as they provided the critical care for their patients. If there were Zoom trainings for caregivers to prepare them for the nuances and changes in the pandemic, caregivers did not have quick access to computers and trainings to remote information communication technologies (ICT) were left out of the digital transition.

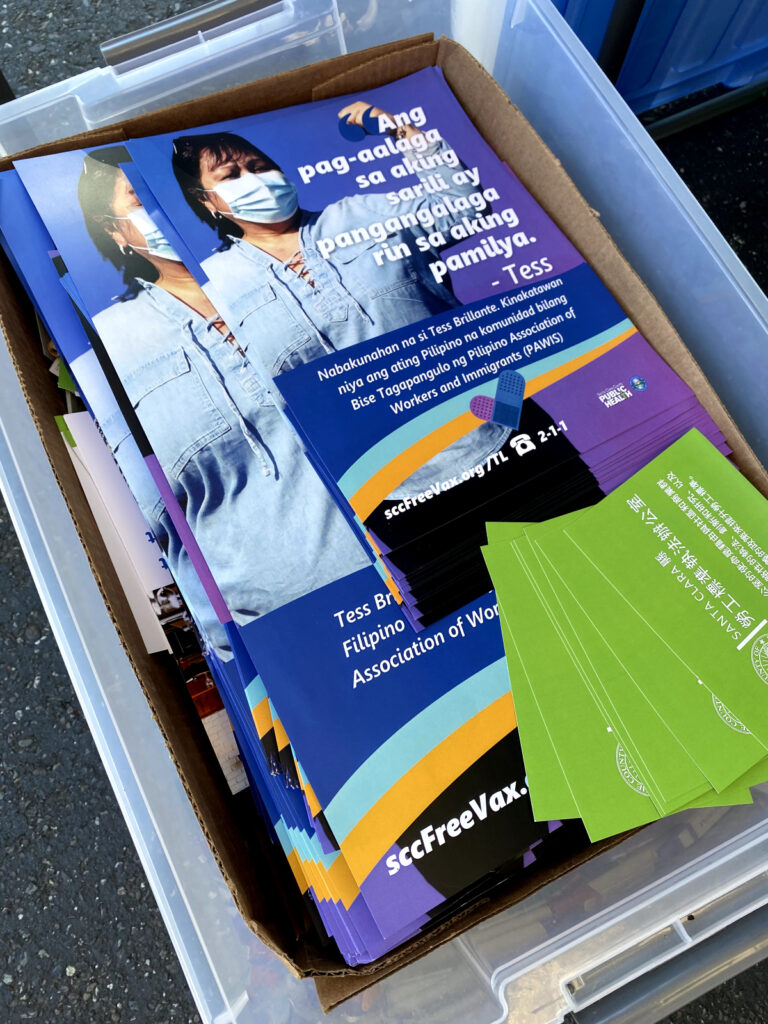

Still, it was the innovation of Filipino migrant worker organizations like, Pilipino Association for Workers and Immigrants (PAWIS) in the Silicon Valley, Bay Area, that helped caregivers address these obstacles. Organizers developed one-on-one outreach to keep in touch with caregivers in the PAWIS organization through group text apps such as Groupme or Whatsapp. When PAWIS worker leaders were convinced that the lockdown and the pandemic would not only last a short period, and therefore the organization explored how to convene their members through Zoom. PAWIS leaders activated a Filipino cultural practice called, “kuwentuhan,” or talk-story through monthly Zoom events for caregivers to attend.

Although, the virtual Zoom space isn’t the same as in-person socializing, caregivers, and many Filipino immigrants before them, were already familiar with translating some of their day to day lives into some digital and virtual format, given their relationships with their families in the Philippines are mediated by ICTs like Facebook, FaceTime, and Instagram. The “kuwentuhan” events not only sought to create social spaces for caregivers to connect, it also offered practical advice from labor lawyers with regards to navigating fast changing federal and state-level benefits for unemployment or paycheck assistance. Both, the opportunity to connect with other caregivers and the legal advice, were compelling reasons to come together.

When in-person meetings were allowed, PAWIS organized Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) drives where they would not only distribute essential equipment for caregivers, there would be homemade Filipino food included in what they called “care packages”. If caregivers were not able to make it out to the drive, they would receive one on their front doorstep of the facility they worked at. In these many ways, the innovation and ethics of care among caregivers made visible the frontline work of Filipino migrants.

Valerie Francisco-Menchavez

PhD San Francisco State University vfm@sfsu.edu

All the images: Valerie Francisco-Menchavez

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

One comment on "Invisible Frontliners: Filipina/o Caregivers in the United States and Collective Care"