Claudia and Care

Nancy Folbre

12 October 2023Hearty applause for the honor paid to this year’s winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics should be combined with a critical look at her work.

Claudia Goldin is a feminist trailblazer in many ways. She provided some early and important documentation of the “marriage bars” that state and local governments put in place in the early twentieth century, forcing school teachers, among others, to resign if they married or became pregnant. Along with her co-author Cecilia Rouse, she conducted a fascinating empirical analysis of the impact of requirements that symphony orchestra auditions to be conducted beyond a screen to conceal performers’ gender (more women performers were hired!). Her “pollution” theory of discrimination explains why men might feel diminished by the entry of women into their occupational spaces. In conjunction with Lawrence Katz, she demonstrated the economic “power of the pill”—the effect of oral contraceptives on women’s employment decisions. Much of her recent research rightly emphasizes the ways in which women’s historical embrace of family responsibilities has lowered their lifetime earnings.

Her optimism, reflected in phrases like “a grand convergence” and a “gender revolution,” and most recently, “why women won,” has a powerful appeal. But while we all have good reason to celebrate gains in women’s legal rights, Goldin’s optimism is colored by her focus on mostly white, affluent, highly educated career women like her (and me) who have the resources to offload considerable care responsibilities onto others. Her analysis of divisions among women in the U.S. centers on differences in attitudes, with little attention to economic constraints based on race, ethnicity, citizenship, or class. As pointed out recently in an article in the Hindustan Times, her arguments are not easily applied to women in the Global South.

My brief review of Goldin’s latest book, Career and Family, explains why I think she overstates the role of longer employment hours in explaining why men continue to earn substantially more than women in the U.S. I’m not persuaded that long work hours are rewarded in the labor market simply because they are more “efficient.”

Goldin sees commitments to family care as a personal choice—a costly preference—rather than an important and undervalued contribution deserving of more public support. Like many economists working in the neoclassical tradition, she emphasizes tradeoffs between equity and efficiency, asserting women earn less than men because a) they are not willing to put in as many hours on the job and b) employers are not willing to sacrifice efficiency in order to play nice.

The Economist magazine counted Career and Family among the best books of 2021, summarizing it as follows: the gender gap in earnings is “the result of couples making a rational choice over how to maximize household income.”

One can agree that people try to make rational choices and still examine the constraints they face. Many feminist researchers in the U.S., ranging from Joan Williams in 2000 to Caitlin Collins in 2022, have shown how interests based on class and gender led to the construction of the “ideal worker” as one unencumbered by responsibilities for family or community care. Research by scholars like Evelyn Nakano Glenn and Rhacel Parreñas on the ways in which inequalities based on race, ethnicity, and citizenship have shaped the care economy.

I will give another article from The Economist the last words:

“Like a radical, Ms. Goldin has identified a structural feature of the economy: “It isn’t you, it’s the system,” she reassures the reader. But she has the liberal’s hesitancy about disrupting a system that is built on choice.”

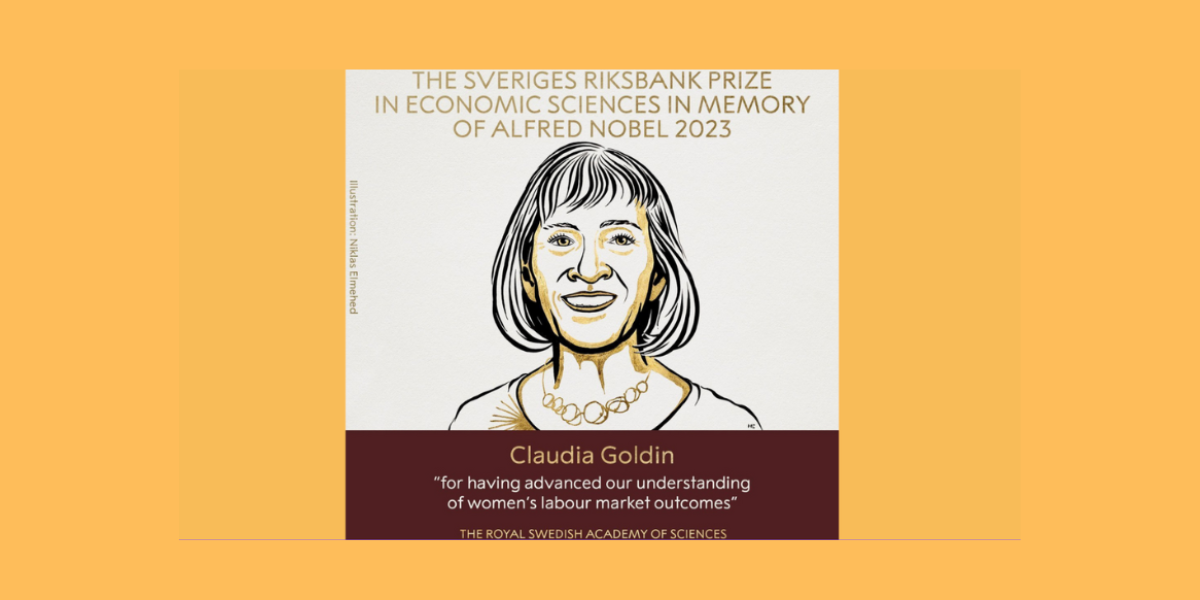

The cover picture is designed by Niklas Elmehed .

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

rcge-admin

From Eileen Boris:

Bravo Nancy! I reviewed Career and Family, critiquing its exclusions of Black and other women of color as well as its class bias in the journal LABOR (December 2022) in which I said: “For Goldin, the culprit is not discrimination, especially since the demise of nepotism and other legal restrictions on women’s work. It isn’t corporate capitalism—after all, women pharmacists improved their standing laboring for branches of national companies. Rather, it is “greedy work,” a time bind that Arlie Hochschild highlighted nearly a quarter century ago, that Goldin finds upending the progressive story she charts on “women’s century-long journey toward equity” (9). This subtitle expands the subject of the dismal science’s economic man but falls short as an intersectional tale by focusing on college-educated, mostly white women’s quest to combine “career and family.”

I then end with: “Technological determinism pervades her analysis, with opportunities expanded from changes in household appliances, commodification of housework, and enhanced reproductive technologies. Finishing this study during the COVID-19 pandemic, Goldin asks that we “make certain that they [women] do not sacrifice their jobs because of care issues and that they do not sacrifice their caregiving for their jobs” (222). She passes “the baton” to men: “to lean out at work, support their male colleagues who are on parental leave, vote for public policies that subsidize childcare, and get their firms to change their greedy ways” (18, 235). Such reforms may increase equity for the better off, but are unlikely to upend larger inequalities.”